Country: Italy

Field of Art: Ceramist

Instagram: @fango_ceramics

Jacopo Cucci, an Italian ceramist, embraces the playful nature of working with clay, choosing the name "Fango" (meaning "mud") to remind himself to have fun and explore through his craft. He creates unique, functional objects full of character and details that reveal themselves over time, using collected materials for sustainability and a personal connection to the materials. Jacopo specializes in stoneware, porcelain, and wild clays, mostly wheel-thrown, and enjoys atmospheric firings. He mixes his own glazes and has fired in wood kilns across Italy, Portugal, and Hungary, even building his own gas-powered kiln for soda firing. This residency is Jacopo's first and he is planning to start with clay, possibly digging or collecting some, and hoping to use the wood kiln and mini gama for firing of his work.

Country: UK

Field of Art: Ceramist

Instagram: @elliewoodspottery

We at Driving Creek Pottery are excited to welcome our first pottery apprentice Ellie Woods from Leach Pottery. Ellie Woods has worked as a pottery apprentice at Leach Pottery in Cornwall since the summer of 2021 learning production pottery full time. Over the past three years, she has mastered technical skills such as creating standard ware shapes, mixing glazes, and firing gas kilns, while also developing her own work. Ellie focuses on making functional stoneware pottery for everyday use. Eager to expand her practice, during her three month exchange at Driving Creek she is interested in exploring new environments, experimenting with different materials, and learning alternative methods of making and firing to further develop her work.

Country: New Zealand

Field of Art: Ceramist

Instagram: @_ferris_ceramics

Patrick Ferris is a New Zealand ceramic artist with a passion for clay that started in his youth. After studying at the Dunedin School of Art, where he graduated with a degree in Ceramics in 2022, his work has evolved to combine traditional pottery with digital techniques like 3D printing. Patrick enjoys sourcing his own materials, using local clays such as Temuka and experimenting with cullet for vibrant colors. He values sustainability and avoids harmful substances in his clays and glazes. His work focuses on functional pottery for everyday use, often wheel-thrown, with a particular interest in form and function. Currently, he is exploring a series of printed objects that warp and collapse in the kiln, aiming to create a wall installation and deepen his understanding of wood and gas firings, flashing, and bright colors. Driven by commercial success, Patrick is focused on creating pottery that is both beautiful and functional.

Country: UK

Field of Art: Sculptor

Instagram: @georgiahodierne

Georgia Hodierne is an emerging UK sculptor who creates vibrant, satirical sculptures that challenge societal norms and the unspoken rules of adulthood. Her work emphasizes the transformative power of play and aims to reconnect adults with curiosity and creativity, often overlooked in busy, work-centric lives. Through storytelling, her sculptures spark conversations and alternative perceptions, encouraging innovative ideas while rejecting the pressure to have all the answers.

Her creative process begins digitally, using sketches and Procreate to explore compositions before choosing materials that align with her conceptual ideas. She works primarily with paper pulp, paper clay, and ceramics, valuing non-traditional techniques to subvert fine art norms and embrace playful, absurd narratives. Her work draws on ancient civilizations, particularly ceramics, as a medium for storytelling, using humor and vibrant colors to challenge established cultural beliefs.

Georgia also values collaboration and community, seeking environments like the Driving Creek residency to exchange ideas and refine her skills. Currently, she is exploring the erotic ceramics of ancient Greece and their relevance to contemporary culture. Born in Wellington, New Zealand, and raised in England, she holds a BA in Fine Art Sculpture and is committed to creating, curating, and pursuing freelance projects. The residency offers her the ideal space to explore new artistic directions and deepen her practice.

Country: Denmark

Field of Art: Ceramist

Instagram: @bmorberg

Birthe Morberg Nielsen is a Danish ceramic artist returning to Driving Creek for her second residency. Birthe's work is deeply inspired by the natural surroundings at Driving Creek, she prefers the use of Coro Gold Clay processed on site for her pieces, and is hoping to participate in a wood and soda firing to capture the essence of plants, trees, and animals in their vibrant forms. Birthe's practice spans a wide range of ceramic expressions, from functional items like plates, mugs, and boxes, to more imaginative sculptures of animals, aeroplanes, and other objects. Her work often features a playful twist, incorporating humor and charm into each creation, inviting a lighthearted and engaging experience for viewers.

Country: India

Field of Art: Ceramist

Website: neetig.com

Instagram: @neetigoclay

Neeti Gokhalay Kheny is a Bangalore-based ceramic artist whose work is inspired by her deep connection to the sea and nature. With a Professional Diploma in Visual Communication from Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Neeti’s artistic journey is influenced by her experiences growing up in a merchant navy family, frequently traveling across the Atlantic, and becoming a certified Advanced Open-Water Diver. Her ceramic sculptures capture the intricate beauty of the underwater world, distilling these experiences into tactile forms that invite curiosity about aspects of nature that many may not often consider.

Neeti hand-builds her pieces, beginning with sketches and planning techniques before moving on to coiling, pinching, and ornamentation with slips and underglazes. Her work is characterized by bold designs, delicate textures, and the use of glazes that interact in creative ways. Firing her pieces in an electric kiln, Neeti documents the entire process, using images, videos, and notes to reflect on what works and what doesn't.

Currently at the beginning of her journey with clay, Neeti is eager to further explore and refine her artistic voice. She seeks to push the boundaries of her work by learning new techniques and experimenting with various firing methods, including wood and reduction firings. Neeti is particularly excited about the opportunity to engage with fellow artists at the Driving Creek residency, where she hopes to expand her understanding of clay, glazes, and firing processes, while developing a cohesive body of work that reflects her love for the oceans and nature.

Exhibition curated by Karl Fritsch

The NOTTAPOTTA exhibition at Driving Creek Gallery is a tribute to the visionary artist, potter, and conservationist Barry Brickell. More than just a showcase of his diverse art collection, this exhibition immerses visitors in Barry’s unique way of thinking and creating—his philosophy of process over outcome, encapsulated in his ethos: “It’s not the thing, but how.”

At the heart of NOTTAPOTTA are Barry’s writings—or as he called them, “wrertings”—a playful and deeply personal form of expression that captures his musings on art, nature, life, and the trains that became such a central part of his world. These words, painted in sloppy clay on the gallery walls, form the base layer of the exhibition, setting the tone for the artworks displayed around, on, and over them.

Barry Brickell was not only a prolific artist but also a passionate collector, gathering pieces that resonated with him over the years. Notta Potta features an eclectic mix of styles and approaches, from paintings acquired from local artists to works gifted by renowned national and international creatives who visited Driving Creek. Many of these artists were drawn to Barry’s unique environment, staying, working, and creating in a space where art and nature intertwined seamlessly.

This exhibition offers a rare glimpse into Barry’s world—one where art was not just about the finished product, but about the journey of creation itself. Whether you are familiar with Barry’s legacy or discovering his work for the first time, NOTTAPOTTA invites you to engage with his vision in a deeply immersive way.

Exhibition Details:

📍 Location: Driving Creek Gallery

🕒 Opening Hours: Tuesday – Sunday, 11 AM – 3 PM

📅 Closing Date: February 29, 2025

Don’t miss this opportunity to explore the artistic mind and collection of one of New Zealand’s most beloved creative figures. NOTTAPOTTA is more than an exhibition—it’s an experience of Barry Brickell’s enduring spirit.

Country: New Zealand

Field of Art: Ceramist/Art Educator

Website: www.connectthedots.org.nz

Introduction:

Andrea Gaskin is an artist and arts educator committed to removing barriers to arts participation and celebrating diverse visual languages. She has focused her practice on arts education, particularly in the areas of brain injury and dementia, and now aims to expand her own artistic journey. A passionate hand builder, Andrea has years of experience in both practicing and teaching handbuilding techniques, valuing the individual expression that each maker brings to the craft. She has held a residency at Studio One Ponsonby in Auckland and integrates her pottery skills into her charity, Connect the Dots. Andrea is soon visiting India to explore combining pottery with textiles, particularly through block printing. Her goals include dedicating uninterrupted time to her pottery practice and connecting with like-minded artists.

Country: New Zealand

Field of Art: Ceramist

Instagram: @samdmakes

Introduction:

Sam Dickenson is a passionate ceramic artist who discovered his love for pottery as a teenager. She went on to study ceramic design at Central St Martins and spent five years designing and creating pottery in London before relocating to Auckland in 2007. After a break from her practice due to family commitments, Sam has returned to ceramics with the support of the Auckland Studio Potters. She now explores handbuilding, working with slabs, plaster, and ceramic molds made from found and self-created forms. Sam enjoys creating functional pieces like mugs and platters, valuing the experience of using and enjoying his work. She aims to loosen up creatively, connect with the community, and embrace a fun, open-minded approach to his craft.

Country: United Kingdom

Field of Art: Sculptor

Instagram: @georgiahodierne

Introduction:

Georgia Hodierne is an emerging sculptor whose work challenges societal norms through vibrant, satirical sculptures. Her practice explores the transformative power of play, reconnecting adults with their innate curiosity amidst a fast-paced world. By questioning culturally established narratives and offering playful, absurd scenarios, Georgia invites alternative perspectives and fosters conversation. She combines her background in digital drawing and collage with material choices like paper pulp, clay, and paper mache, which she uses to create pieces that subvert traditional art forms. Drawing inspiration from ancient civilizations and the role of ceramics in storytelling, her work conveys humor and challenges norms. Passionate about collaboration, she is eager to contribute to communities like Driving Creek, where creative exchange thrives. Currently, she is exploring the artistry of ancient Greek erotic ceramics, aiming to contextualize these historical creations in a contemporary setting. Raised in England and born in Wellington, New Zealand, Georgia has completed her BA Hons in Fine Art Sculpture and is actively pursuing creating artworks while curating shows and engaging in freelance projects.

Country: United States

Field of Art: Ceramist

Website: www.girlpots.com

Instagram: @girlpots

Introduction:

Sasha Polonko, founder of Girl Pots, is a Costa Rican-American ceramicist based on Whidbey Island. Her work is deeply rooted in sustainability and her connection to nature, reflecting her Costa Rican heritage. Sasha creates her own glazes and clays from raw materials she forages locally and globally, with a focus on durability, comfort, and beauty. Influenced by pre-Columbian ceramics, particularly from Costa Rica, Sasha blends contemporary pottery with ancient aesthetics. She experiments with found clays and natural glazes, sometimes combining them with commercial products. Her process involves gathering materials, developing clay bodies and glazes, and choosing firing methods that best honor the materials. Sasha is eager to explore pre-Columbian pottery techniques further, aiming to create a collection using locally sourced materials and traditional firing methods.

Country: New Zealand

Field of Art: Multi-disciplinary Artist

Instagram: @cindyhuang.studio

Introduction:

Cindy Huang is an interdisciplinary artist whose work spans installation, painting, performance, and social sculpture, exploring themes of exchange, generosity, and adjacency. Her research delves into the histories of Chinese migrant communities in Aotearoa New Zealand, particularly the relationships between Māori and Chinese communities. Huang's practice includes large-scale installations that blend ceramic sculptural objects with social engagement and community building. She draws from historical accounts of Chinese life in Aotearoa and the concept of being tangata tiriti. Currently, Cindy is focused on expanding her studio practice, particularly in clay, and is developing a new body of work exploring migrant relationships with the landscape, blending regional New Zealand painting with Shan Shui (Chinese Mountain Water) aesthetics and personal identity.

Country: Sweden

Field of Art: Ceramist

Website: clayspacestockholm.com

Instagram: @clayspace.stockholm

Introduction:

Yvonne Matstoms is a Swedish ceramic artist whose creative journey began after the loss of her spouse, finding solace and purpose in clay. She feels strongly that art and to creativity is a true connection with the mystery and the greater in life.With a background in art history and a deep aesthetic appreciation, she realised her own artistic potential later in life. Yvonne draws inspiration for her work from organic forms, the Arts and Crafts movement, archaeological findings, and Japanese everyday ceramics. Yvonne primarily creates functional, beautiful items like bowls and vases, blending several techniques such as throwing, coiling, and slab-building in her work. Her goal is for her work to be cherished and displayed, even when not in use. Currently, she’s exploring sculpture, particularly a series inspired by the need for protection in today’s turbulent world, including sculptures of angels and swans symbolizing strength and blessings.

Country: Australia

Field of Art: Ceramist

Website: silvesterart.com

Instagram: @silvesterart

Introduction:

Sara Buchner (SilvesterArt) is a multidisciplinary artist whose work is inspired by dreams, creating small, heartfelt illustrations and prints. Drawing from the Wiener Werkstätte and the publication Ver Sacrum, her pieces blend clean lines with narrative, resulting in expressive and animated works. Sara incorporates discarded materials, like scrap wallpaper and linoleum offcuts, into her watercolors and linocuts, adding a surreal, everyday quality to her art. Her printmaking utilizes non-toxic ink on small-scale lino and plywood blocks, while her ceramics feature slab-built, architecturally inspired sculptures, vases, and planters. Sara is currently focusing on incorporating native plant motifs and landscape-inspired sculptures into her ceramic work and was looking to explore new mediums and techniques during her residency at Driving Creek.

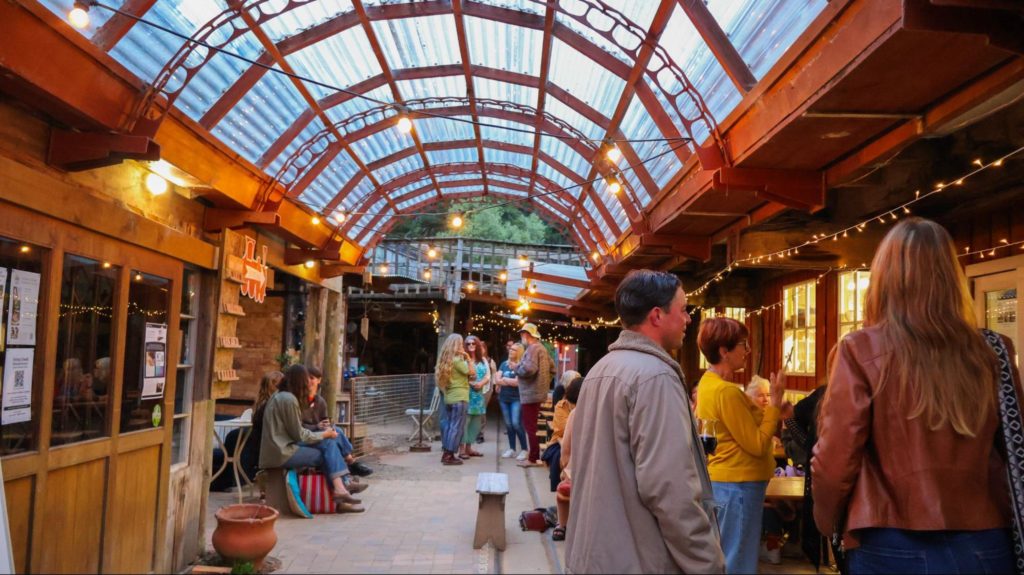

Driving Creek’s 50th Anniversary was a weekend to remember, bringing together our community to celebrate the legacy of Barry Brickell and the enduring impact of Driving Creek. The event offered something for everyone, from thought-provoking panel discussions to creative exhibitions and engaging activities.

One of the highlights was the Nottapotta Exhibition, the first of its kind, showcasing an eclectic selection of Barry’s personal collection, including pots, paintings, sculptures, and writings. This carefully curated exhibition, on display in the Driving Creek Gallery, offered a unique insight into Barry’s artistic world and featured works by celebrated New Zealand artists such as Ralph Hotere and Colin McCahon.

The panel discussions provided a platform for rich conversations about Driving Creek’s past, present, and future. Moderated by notable hosts, these sessions featured a diverse range of panellists. Discussions explored Barry Brickell’s legacy, Driving Creek’s evolution over the years, and aspirations for its future. These conversations captivated audiences and sparked ideas for preserving and growing Driving Creek’s vision.

Guests also enjoyed live music, storytelling, and an oral history recording project in the Memories Lounge, which helped capture the voices and experiences of those who have been part of Driving Creek’s journey. The kiln firings, workshops, and creative activities allowed attendees to get hands-on with pottery, a fitting tribute to Barry’s passion.

Thank you to everyone who joined us to celebrate this milestone. Your presence and support honour Driving Creek’s rich heritage and inspire its future. Stay tuned for more exciting initiatives as we build on the momentum of this incredible weekend!

The Coromandel Peninsula, known for its stunning landscapes and rich biodiversity, is home to one of New Zealand's most iconic trees: the Kauri. These magnificent giants showcase the region's natural beauty and play a vital role in the cultural and ecological landscape. Driving Creek has played a part in replanting Kauri and other native trees through the hard work of Barry Brickell and his family and friends.

History of Kauri

Kauri trees (Agathis australis) are among the largest and longest-living trees in the world. Kauri can grow up to 16m in girth, 50 metres tall and can live for over 2,000 years. Tāne Mahuta is the largest remaining Kauri tree and lives in the Waipoua forest measuring 45m tall. Kauri trees once covered 1,200,000 hectares of New Zealand. Now only 7,500 hectares of mature Kauri trees remain due to the logging industry. These ancient trees have thick, straight trunks and distinctive, spreading crowns. The wood of the kauri is renowned for its durability and resistance to decay, making it highly prized for construction and carving.

Logging of Kauri

Add dates - in the 18-1900’s? To harvest the wood, teams of bushmen would saw through the logs with a double-ended saw for upwards of 12 hours per log. Once the Kauri logs were felled in flatter regions they were towed out of the forest using a team of bullocks or horses. In the Coromandel region, the terrain is quite extreme so towing wouldn’t be a viable transport option. A method used to get the logs out of the forest was ‘driving’. Driving Creek is named after its past use in driving Kauri logs down to the harbour. Creeks were dammed up in the hills and filled with logs. Huge volumes of water were then released, washing the logs downstream to be milled or exported. Thousands of logs were sent down to booms below, though only 20% were estimated to arrive in a usable condition. In addition to the wood, the Kauri tree was also prized for its gum or sap. From the 1840s, kauri gum was exported to Britain and America to make varnishes. Between 1850 and 1950, 450,000 tons of gum were exported.

Cultural Significance of Kauri

Kauri trees hold deep cultural significance for Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand. They are often associated with spirituality, and their timber has been used in traditional carving and construction. The Kauri gum was also used to make ink for Tā Moko, a traditional Māori tattoo. The gum was burnt and the ash was combined with animal fat to make ink. This ink was tattooed into the skin and as it hardened, caused a raised effect. Māori people would also use the Kauri sap for medicinal purposes and chew on it like gum combined with a plant called Puha to cure stomach aches and headaches. Kauri gum was also used for cooking and lighting because of its flammable properties.

Kauri Dieback Disease

Kauri forests are rich ecosystems that support diverse plant and animal life. The trees provide habitat for various species, including birds such as the Tūīi and Kererū, as well as insects and other wildlife. The days of Kauri logging are now gone as the Department of Conservation has protected Kauri trees since 1987. Although logging is now banned, Kauri forests face significant threats from pathogens like Kauri dieback disease, which has led to widespread tree mortality. Kauri dieback disease poses a significant risk to our Kauri. It is a microscopic pathogen that is spread via infected soil. The pathogen that causes Kauri dieback disease, was first recorded on Great Barrier Island in the early 1970’s. There is no known cure for Kauri dieback so all Kauri trees which become infected will die. To help reduce its spread, visitors must carefully and respectfully follow the rules when visiting Kauri forests- not walking directly on Kauri roots or near Kauri trees, disinfecting their shoes and staying on formed tracks. Conservation efforts are crucial to protecting these ancient giants and the unique ecosystems they support.

Kauri at Driving Creek

Driving Creek is nestled in the heart of The Coromandel and is more than just a tourism operation. It’s a testament to the late Barry Brickell's pioneering spirit and unwavering dedication to art, engineering, and conservation. Barry set out in the 1970s to return the Driving Creek land to pre-colonial times by replanting the 24-hectare property with over 27,000 native species including Rimu, Totara, Matai, Miro, Kowhai and Kauri. “The whole district, including my block, had undergone 150 or so years of savage exploitation that was, in fact, ecological plunder. From virgin kauri forest to cut-over and logged forest, to repeated burn-offs, to freshly ‘broken-in’ farms, to abandoned, weed-infested, highly eroded hills, to 60 or so years of regenerating scrubland and fern. When I moved on to the land, the better parts were in tall Kanuka forest, which is really mature scrubland with the merest fraction of the diversity of plant and animal life of the original forest. Aware of this ecological history through study, my vision became fixed on reversing the decline of biodiversity.” - Barry Brickell.

Following Barry’s wishes after his passing in 2016, Driving Creek is now a not-for-profit organisation that delivers on its vision to protect and enhance the environment through pest animal and weed control and enrich the artistic community with our unique artist residency programme. We continue Barry’s conservation legacy of protecting and enhancing our native biodiversity by operating intensive pest animal and environmental weed control programmes, performing environmental research, running free conservation events, and connecting people with New Zealand’s natural qualities through enriching, educative and unique experiences. Today, the property is covered in second-generation native forest and is QEII covenanted to protect the land for perpetuity. Driving Creek continues Barry’s vision and commitment to the Tiaki promise to protect, maintain and enhance our natural environment, be a community leader and centre for understanding and contribution to conservation initiatives, and continue improving the health and wellbeing of our local community and visitors.“To inspire others to heal and respect the land by showing what is being done and why. Appropriate utilisation rather than exploitation is demonstrated. Showing and telling is aimed at making the viewer and listener think and hopefully act.”- Barry Brickell.

Did you know there are three types of frogs in The Coromandel? Two are native, and one is an introduced species. The frog you often see in the garden is likely the green and golden bell frog, a species introduced from Australia. These frogs, with their green or yellow bodies and gold or bronze patches, are now common across the North Island. Bell frogs are the largest in New Zealand, growing up to 10 cm long with a loud call. Females can lay between three and ten thousand eggs, which hatch into tadpoles in about two days and become frogs within two months.

Rare Archey’s Frog Discovery at Driving Creek

Our native frogs are very different; they belong to an ancient group that has remained unchanged for 70 million years. These small, silent, and cryptic frogs include Archey’s frog, our smallest and rarest, growing up to 3.7 cm long. Archey’s frogs, typically found in damp forests 400 meters above sea level, were recently discovered on Driving Creek land—a thrilling find as they are a threatened species and extremely hard to spot!

Hochstetter’s Frog Thriving at Driving Creek

We also have Hochstetter's frogs at Driving Creek. These semi-aquatic, nocturnal natives are brown-green to brown-red with warty skin and dark bands. Much smaller than bell frogs, adults are less than 5 cm long. Unlike bell frogs, Hochstetter's frogs don't croak and skip the aquatic tadpole stage. They lay only about 20 eggs per season, and it takes 3-4 years for the froglets to reach full adult size. Hochstetter’s frogs are more frequently seen at Driving Creek, as they are slightly larger and have consistent habitat preferences.

Protecting Our Native Frogs

We are fortunate to have such remarkable creatures here on the property. To protect these rare native frogs, we actively engage in extensive trapping work to reduce the presence of introduced predators, which are a key threat to their survival. By enhancing predator control at key sites and restoring stream habitats, we strive to create a safer environment where these native frogs can thrive.